Never Waste a Good Crisis:

The Golden Opportunity for the C-Suite to drive for a New and Better Future

By Dr Darryl Cross

(Crossways Consulting)

&

Stephen Dowling

(ETM)

It was Sir Winston Churchill who said, “Never waste a good crisis”. Nothing was more true than in these unheralded times. What have we learned? What have we unlearned? What have we re-learnt? Where can we grow? How or what can we develop? What do we take from all of this?

Apparently, the Chinese symbol for “crisis” is composed of two characters, one signifying “danger” and the other “opportunity”. As we well know too, there are two sides to every coin, so what is the flip side for this pandemic called COVID-19? What is the opportunity?

Throughout history, awful events have contributed to real transformations. For example, the bubonic plague of the 1300s led to the modern employment contract. Cholera epidemics of the mid-1800s provided us with urban parks, gardens and open spaces along with improved infrastructure. With the 1918 Spanish Flu, there was a revolution in healthcare.

This global pandemic has already had a massive impact on the world economy and the full ramifications of which are still to be fully understood. What will be the long-term impacts? What will the new normal look like? What will be next? Are we now living in a world which will keep throwing up new unpredictable “black swan” events?

These events fundamentally change reality, and, what has worked in the past may no longer work in the future. Knowledge & skills can become obsolete overnight, and to ensure one stays relevant we need to be open & willing to unlearn the past.

Can & should we use this as an opportunity, a catalyst to continue to disrupt ourselves, and our organisations, so we can drive towards a better future?

“Disruption does not apply to organisations.

The truth is it applies to individuals.” Barry O’Reilly

What’s the Immediate Lessons to be Learned by CEOs?

It was a stop and prop that no-one saw coming. We all stopped. Businesses stopped, jobs stopped, social engagement stopped, churches and conferences stopped, gyms and exercise stopped, sports and recreation stopped.

Never before in our lifetime have we ever had a full-stop like now. And we’re all in it together. Not just one country, or one state, or one locality. All of us. The whole planet.

What have we recognised first up?

- Our mental model (beliefs) have changed.

As a result of COVID, our mental model (& core beliefs) about the world have been fundamentally challenged and they will have been changed. We have unlearned some beliefs and relearned some new ones. Not having a choice in the matter has of course helped speed this transition, but the big part is that we’ve done it, and proven to ourselves that we can, in fact, do it when we have too.

It’s simple to see in the work-from-home or remote working. It’s taken over a decade for most leaders to accept that it might actually be a workable solution and previously, some have allowed their staff to work from home for, say, a half-day or even a day a week.

Then Bam!

Everyone has to work from home. Believe it or not, the world kept spinning and employees kept working, and from most reports, employees are more productive and happier not to mention less traffic on the roads and less wasted time getting to and from work.

What other beliefs are we holding onto? What other areas do we need to examine? What other blind-spots do we have?

- We have all adapted quickly.

Change for most of us is slow. We are creatures of habit. However, not so with the pandemic. For example, we have been able to adapt with two years of digital transformation in just 2.5 months. We suddenly embraced software like Zoom or Microsoft Teams and the like. Leaders are recognising that these video conferences actually do work and that maybe we really don’t have to spend time waiting in airports and catching planes spending valuable dollars on travel and accommodation.

“We saw 2 years of digital transformation in 2 months”

Satya Nadella, Microsoft CEO; 30th April 2020

One South Australian food packaging company called Detmold for example, turned to making Personal Protective Equipment with face masks for front-line workers. Apparently, Dyson (the vacuum cleaner and appliance manufacturer) set about making respirators for ICU departments in hospitals.

The message is clear. We can adapt and quickly if necessary.

Where Are We Now?

- Things were already broken.

Many C-Suite would not always agree that things were broken. But think about it. Consider for example, the lack of work-life balance that is not sustainable and the low levels of staff engagement across various industries and sectors.

Firstly, the evidence of a broken system is the increasing levels of stress and burnout. Most organisations were struggling to cope prior to COVID, but now it’s getting worse.

The previous VUCA world (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) was playing with our minds and causing us stress, anxiety and pressure with a lack of work-life balance for many. The stress and burnout had become overwhelming for many.

What’s interesting too is that given we have all had to stop, many are now enjoying the return to a slower life and a life where it is not so fast-paced and where they have time to re-connect with their families and their children.

Secondly, there are poor levels of staff engagement across the global economy. According to Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace, only 15% of employees are engaged in the workplace. What does that do to the bottom line?

Employees are now able to view a company’s culture through social media where businesses are more transparent than ever before. Not surprisingly, employees are voting with their feet to work for businesses where they feel engaged and empowered. How big an issue is this for organisations? Will you be able to attract and retain bright, creative and capable people?

And whether we like it or not, the world will continue to change at an increasing rate. Remedy? We need to find a better way. It was not sustainable the way it was.

- It is clear that the top roles in any company or organisation outdistance the capabilities of any single person.

Part of the dilemma of the outdated command and control kind of leadership that we have all known, is that in a VUCA World, no-one individual can do it all. No one leader can now be across it all.

As Manfred Kets De Vries states, “In our global highly complex world, the heroic leadership figure has increasingly become a relic”.

An underlying assumption of the traditional top-down hierarchical model is that the further up the hierarchy an individual goes, the more they know, the more that they can make the best decisions in the interest of the organisation. How can this remain valid now in our rapidly changing and complex world? It is no longer valid. It’s a myth.

It is little wonder therefore that a growing number of executive leaders are either declining the top job or choosing to opt out.

- The traditional command and control model of management is no longer relevant.

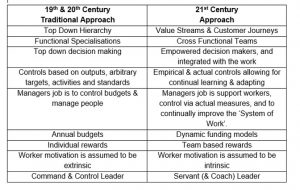

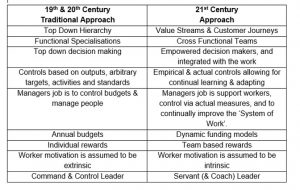

The world has fundamentally changed, yet we are still (by and large) using an outdated management model based on the thinking, principles & processes from the 19th & 20th century. This model is characterised by adopting a “top down” functional hierarchy based on a specific “command and control” way of operating at its core.

Would you believe the military actually abandoned “command & control” after the Napoleonic wars realising how ineffective it was in a fast-changing dynamic environment, but yet it’s still seen by the majority of CEO’s as normal and accepted best practice today.

Most organisations are trying to have a foot in the 19th and 20th Century camp while trying to cope with the 21st Century (see the Table below).

The big problem is, these distinct models will never work well together. They are fundamentally very different ways of thinking, working & leading.

Answers to these questions are very different under both approaches. How should we best organise ourselves? How should we assign & fund work? How should we control & manage work? What is the role of leaders & managers? The answers to these questions are very different and they will have very big ramifications within organisations.

If the CEO still has a mental model based on a top down hierarchical traditional “command & control” approach, then he or she could be the company’s biggest obstacle.

As a CEO, it is important to accept that the reality has fundamentally changed and the traditional management approach is no longer “fit for purpose”, and major systemic changes will be needed if they want to evolve to a 21st century approach. If, as a CEO, he or she is currently on the left had side of the Table above, then this transformation journey will need to start with them! As the most senior leader in any organisation, it is critical to get onto the right page. Unlearning the old and relearning the new.

Where Do We Want to Get to?

As the great W.S. Deming once pointed out, “mankind invented management, so we can re-invent it”.

Here are two inspiring examples of people who are doing just that:

John Seddon from the United Kingdom is a thought leader in relation to leadership. His thesis for this new age stacks up. He has re-defined the work of leadership and argues that we need a transition from “command and control” to “motivate and mentor”. He this process the Vanguard Method. What does this mean? Now that leaders are in uncharted waters like never before, they have an opportunity to re-build alignment and commitment from their people by dispensing with the traditional tools of bureaucratic control. Instead, he proposes focusing on the system itself.

For example, the Vanguard Method was implemented by Owen Buckwell, the Head of Housing at Portsmouth City Council in England. Over 40,000 people rely on him for warm, safe and comfortable homes. Each year, he is responsible for dealing with 17,000 blocked toilets and 100,000 dripping taps in 17,000 council homes. Buckwell got curious about how his customers could be more satisfied, and instead of focusing on managing people and budgets, he focused on the design and management of work.

In this way, he listened intently to phone calls from complaining customers over an extended period of time. He learnt that at least 60% of the complaints were preventable. Hence, Buckwell went about designing a new work system that gave value to the customers (not value to his record-keeping, data and statistics around which the previous system was designed). Buckwell rearranged the work system in order “to carry out the right repair at the right time” for the tenant, not to try and receive favourable reports from the Government.

The result? Interestingly, not only do repairs now get done on the day and the time when the customers want, but Buckwell also halved his costs. Further, this all meant that he was able to change his supply chain and carry 25% less stock.

Zhang Rummin, CEO of Haier took over the struggling company in 1984. Haier is a whitegoods appliance maker based in Qindao, China, and is currently the world’s largest appliance maker with a turnover of (US) $35 billion with 75,000 employees. It wasn’t always so. The trigger to the turn-around was not a pandemic, but the fact that the company was making poor and inferior products. Rumour has it that in the beginning, Rummin lined up scores of appliances in a row and in front of all the staff got employees to smash up these appliances with sledge hammers; the point was that that was all that these appliances were good for and that things were about to change.

Now the company has about 4,000 self-managing microenterprises. About 250 are market facing (“users”) and the rest (“nodes”) supply them with components and services like IT and HR support. Users can hire or fire nodes or even contract with outside providers if they deem that IT and HR for instance are not providing adequate services. The Nodes revenues are tied to their Users/ success.

Ultimately, everyone is accountable to the company’s customers. Everyone is encouraged to be an entrepreneur. All targets are ambitious, and rewards are tiered, performance based and potentially hefty.

The result? For the last decade, the gross profits of Haier’s core appliance business have grown by 23% a year while revenue growth has increased 18% yearly and there has been $2 billion in market value from new ventures.

We see these as two foremost examples of people who are re-inventing management and finding a better way.

How Will We Get There?

We are very aware of the massive challenges that exist here. On the face of it, the task at hand appears very overwhelming, maybe even an impossibly.

So, where do we start? We start by getting the foundations right.

In his book “The One Thing“, Gary Keller says that success at anything is all about lining up a series of dominos.

We need to start by figuring out what are the first most important dominos that we need to focus on. At any point in time, you should be able to identify ‘1’ thing which is most important at that exact moment in time. What are the starting foundations which everything else will build on? What will make everything else easier down the track? What will help us build momentum? Identifying these is of course, the big challenge.

To learn a fundamentally new way, we need to first be open and willing to “unlearn” the past, otherwise it will never work. You will just end up trying to map new thinking onto your old mental model which will never gel.

We all act based on our mental model of the world. What do we believe is true? What do we believe is the best way to get stuff done? How do we best achieve our outcomes?

“The world as we have created it, is a process of our thinking. It cannot be changed without changing our thinking.”

Albert Einstein

Before we can learn a new way, we need to unlearn the old. This is the very big challenge as it’s not something which is typically easy to do. We each need to find our own path up the mountain and the journey is everything.

To be able to change your mental model you need to see & experience things for yourself.

However, as we’ve said earlier, the great news is we’ve proven to ourselves with COVID that we can do it. We can change our mindset (beliefs) & behaviours. Not having a choice did of course make it a bit easier than normal, but let’s see this as the great opportunity that it is and build on this for the future.

What Will Stop Us?

Even though all the rules have now been broken and there is a grand opportunity to create a new way of operating, the majority of leaders will fail themselves and their businesses by retreating back to what they knew in the past.

1. Overcoming Fear

Like a rubber band that is stretched, leaders will ping back into their original shape. Why so? Fear.

Fear that they will somehow lose control if they don’t do as they’ve always done. Fear of looking stupid or ignorant or less knowledgeable if they try things differently. Fear of looking vulnerable. Fear of riding on uncharted waters where they might be out of their depth.

“What if I muck up?” “They all look to me as their leader, so I have to look like I’m in control.” “What if it didn’t work out?” “I don’t know where to start.” “I’m stuck.”

As one book title aptly says, “feel the fear and do it anyway”.

2. Overcoming Learning Blocks

It was back in 1991 when Chris Argyris stated in his Harvard Business Review article that, “Because many professionals are almost always successful at what they do, they rarely experience failure. And because they have rarely failed, they have never learned how to learn from failure”. True words decades later.

It is a truism too that we learn more from our failures than from our successes. Sadly though, the C-Suite will generally do all they can to continue to look good, look like they are in control rather than being vulnerable and acknowledging to themselves and those around them that in these unheralded times, it is about experimentation, trial and error and trying things differently. This kind of transparency and honesty is real leadership which is endearing to followers.

The basis of success for the C-Suite is usually about clear vision and goals, time-lines set in place, experience-based judgement, the ability to convert data into useful patterns and themes in order to make decisions, but in a pandemic, this evaporates overnight. Then what?

Things are now happening so quickly that time-lines become redundant and the ground is constantly moving which means executives either become paralysed or scramble frenetically to try to re-plan. Hence, time-tested approaches involving careful analysis and consensus building are no longer relevant.

Leaders with a healthy ego, and a sense of who they are, will not balk at trying something different now. Level 5 leaders (see “Good to Great” by Jim Collins) won’t retreat from experimenting and seeing how they can dispense with the traditional management methods in order to adopt new and better ways of thinking, working and leading.

To be a great leader now and into the future, the most important attribute we believe is courage. To be able to break free of the old outdated traditional models will be exceptionally challenging and brave leaders are needed to lead organisations on this path.

“Courage is the first of human qualities because

it is the quality which guarantees the others.” Aristotle

Summary

If ever there was an opportunity for leaders to try something different, this is it. This is the moment. We wouldn’t have wished this pandemic on anyone, but now that it is here, it provides the perfect springboard for leadership to be brave enough to try a new way.

As a result of COVID-19, all leaders have had to adapt. Limiting beliefs have been smashed and we need to use this as an opportunity to challenge many more beliefs which underpin our existing “command & control” management model.

Mankind invented this model of management so we can re-invent it. The current model was created for a very different time (a world of mass production, economies of scale, & standardised products), and it’s “used by date” has well and truly passed.

Sadly, it is our prediction that most leaders won’t be courageous enough, but those who do, will thank themselves, their businesses will thank them and their stakeholders will also thank them. The future for all involved will be brighter and sustainable beyond this crisis.

So, if you are up for the challenge let’s focus on knocking over these dominos one at a time.

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

Chinese Proverb

How Do You Have the Conversation?

How Do You Have the Conversation?